Interview with Kate Robertson about her biography of Elisabeth Beresford

Back in 2020, Tidy Bag was contacted by a publisher keen to produce a biography of Elisabeth Beresford, wondering whether I might be interested or know anyone suitable to write it. My first suggestion was Elisabeth’s daughter Kate Robertson, who I knew was a writer and was as close to the family history as you can get. So I was delighted when I later heard from Kate that she was indeed working on the book.

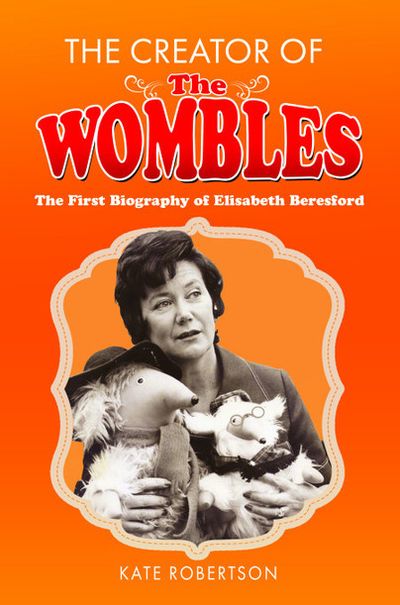

Three years down the line, with The Creator Of The Wombles ready for release in March 2023, I met up with Kate for an in-depth chat about her mother’s life and how she researched the biography.

“I was very happy to take up the reins because I’ve got all the primary source material here, diaries and letters,” says Kate. “So it was obvious that I could be the person to write it - if I could still write! I had a career in trade writing really, and quite a long time ago I wrote some children’s books called Dilbert [the Jumbo Jet]. Ever since those days I had been a trade journalist, because I had a mortgage to pay.”

Kate approached this as a ‘warts and all’ memoir, with her mother’s diaries in particular offering a wealth of first-hand facts, anecdotes and personal insights that we would not otherwise have had access to.

“My mother had made quite substantial notes for a biography, which got to a certain period and then stopped. And then she rewrote and rewrote, and they got vaguer and a bit more odd as she got pretty old. So that had to be sorted out as to what was truth and what wasn’t truth, because like any good children’s writer she was quite happy to take on untruths which made good stories. So even now there may be things there in her youth which are through a coloured prism of the way she wrote.

“And then I thought, well I’ve also got her diaries. She didn’t keep one day to day until my brother was born, about 1956, but after that she wrote about an A5 size Letts diary page - not always on the same day, sometimes a week or two afterwards.

“So that took an enormous amount of reading and it was quite difficult really, it changed my perception about things. When you start to read somebody else’s diary it’s bad enough but when it’s your mother’s… but you know, I had to do it, if I was going to tell the truth about her. And really no daughter should read her mother’s diaries. I mean it was very jolly on many occasions, but it was quite a sad process.”

Kate confirms that she and her brother Marcus would not have allowed anyone else to read the diaries. What surprised her the most?

“I knew that the marriage wasn’t a happy one - you know that as a child - and it eventually went down the drain. And I knew that my father was not being faithful but I didn’t realise how quickly, in the late 70s, she started having affairs.

“What also surprised me a bit was just how much her mother had an effect on her. We all knew that Granny had had a tough time, and she lived with us in the house. I can remember, as a child, we did what she said. And this is what Mum had had, all her life. I think she had such an effect on my mother as a child that all she wanted to do was to please her mother. And when she died, she felt a huge amount of guilty relief.

“The other thing which is amazing was just how hard she was working. That was a revelation. I knew as a child you didn’t get to see Mum very much because she was working, but there were lots of other people in the house and that didn’t really worry me. But it was a big treat to see her.

“And of course, once the Wombles became successful the business side of things was very tough. All you get in the diaries is ‘all I want is for my creations to be left alone, to keep the integrity of them, and all they want is to make money out of them’. She couldn’t bear all the meetings with the people who were running Wombles Limited. And she was under strain to produce stuff all the time, and that took its toll a bit.”

Elisabeth (known as Liza, or Lizzie when she was younger) had also written regular letters to her family, which provided further details. “Her letters were always upbeat because Marcus and I were away at school, so she wrote jolly things in case we were homesick. So that was a good source, to balance the diaries against the letters. And there were letters to not just Marcus and me but to my father, although I haven’t got many of those, and to her mother and to her mother-in-law. I’ve got files and files of them.

“Then there were scrapbooks and photo albums, those were newspaper reviews, or pictures of her opening a fete or something. There was nothing really new in those. Mum was a great snapper, she would take photographs of anybody and everybody all the time, and me too. So the sad thing I discovered was that either she’s taking the photographs or I’m taking the photographs but never the twain shall meet. And it’s only when we were very small, there’s a family one of all of us.”

All of Liza’s professional paperwork was donated to the archive at Seven Stories, the National Centre for Children’s Books, in 2015. Kate explains: “There is some material which has not been included because it’s up in Newcastle, and with Covid and everything I never got there. There were cabinets of correspondence to publishers and so on. But most of that stuff is about her romantic fiction; she wrote loads and loads of short stories for magazines. And of course there is other correspondence with [Wombles publisher] Ernest Benn which I won’t have seen, but then most of it is in her diary.”

The middle part of the biography really conveys Liza’s busy lifestyle as a wife, mother, daughter and freelance writer and broadcaster. “I hope what’s come alive is the 50s, 60s and 70s and how it was lived,” says Kate. “I can remember a lot of it myself and I had to be very careful not to put my memories in instead of hers sometimes.

“Obviously I had to build up to the Wombles and then there was less the other side, so I left out some of her life in Alderney. I wanted to really focus on how it came about that she could do the Wombles - what was it about her? All the stories of her life and all these things sort of fed into it, especially the whole idea of recycling and the environment and so on.”

Money worries were a recurring theme throughout most of Liza’s life. While her husband was a big spender, their income was variable and Liza never lost the wartime ‘make do and mend’ mentality, which would have such an influence on the Wombles’ way of living. In her childhood, her mother Trissie had supported the family by taking in paying guests, particularly after her father walked out.

“I suppose without Granny’s input there might have been no Wombles. Because they had to make ends meet. So we were taught to be very careful and economic with everything, and to reuse things, not throw them away when they could have any possible use. And also, she instilled in Mum this really hard work ethic.”

During the Second World War, young Lizzie had grown from an adventurous though sometimes scared 13-year-old schoolgirl, who experienced several bombings, to an independent 19-year-old serving with the Women’s Royal Naval Service in a Morse code listening station.

“I think she couldn’t wait to get away from home,” says Kate. “Being in that boarding house atmosphere, surrounded by all these rather eccentric old people, when her brothers had left home - to get into the real world (or semi-real world) must have been such an eye-opener about what was ahead, what the potential could be for life.

“She had that experience of, very important, but having fun as well. I think that was the first time she felt she worked with a team. Like you do when you first start work, you get a gang and you’re having fun. And they worked hard and played hard. Especially being naval ratings and Wrens, there were lots of parties and things, but those shifts were long and hard. So the war gave her friendship and fun.

“I remember my mother used to do this ‘dah-dit-dah-dit’, the Morse code thing. She’d hear something, she’d hear the radiator pipes going. And she’d go, ‘that radiator’s saying…’, you know. That stayed with her.

“She never really said much about what was in the messages. Obviously she couldn’t, because of the Official Secrets Act. But how she was taking down Morse code German; I think she did German to A-level, but I never asked her that question, so I don’t know how that worked. And then, I don’t think she ever went to Bletchley Park, but she got the medal when they issued them, because all their material went there. So she contributed towards the effort.”

Previous profiles have given the impression that Liza was always destined to follow in the footsteps of her father, author JD Beresford. In fact she began post-war work as a mediocre shorthand typist, in fear of losing her job. Her lucky break was being assigned to a publishing department, where a sympathetic boss, ‘Woody’ Woodham, gave her the opportunity to try some reporting.

“Well, she fell into it,” says Kate, “but I think underneath there was the gene of wanting to write. Because her father had been a writer, and a very successful one in his time but then went out of fashion. And I think she loved reading. She wanted to write.

“And then this lovely Woody taught her. I can remember her talking about him with such affection. He really taught her her trade. So what she was lucky about was that there was somebody who could point her in the right direction.

“I don’t think she thought ‘I’m going to be a writer’. I don’t think she thought ‘I’m going to marry a rich man and live the life of luxury’. I don’t think that ever occurred to her. I think she, at that stage certainly, let life happen to her, because that’s what had always happened. And life led her along that path and into writing.”

After a few years of honing her craft with Woody, Liza got married and took on freelance work after Kate was born. “In those days, I suppose there weren’t that many people who were doing what she did, compared to now. It was quite tough for women, because it was a man’s world, especially in the broadcasting side of things. And so she was expected to be Mrs Max Robertson but she wanted to carry on her writing.

“She was never going to fall into that pattern of being middle-class mummy or whatever, whether it was for money or just this need to have her own world. And when Woody had given her this opening, she was very good at then selling herself into things. Through contacts of my father’s to start with at the BBC, she got herself into doing Woman’s Hour and the Today programme, and bits and bobs.

“She could write anything, she could write 15,000 words in a day. Most of the time it was two or three thousand words, but it was all coming out, and I suppose that’s a natural writer for you.

“There were lots of people that she interviewed, and quite a few of them I left out because I hadn’t got written evidence. Reading through the diaries you’ve got things like: ‘I went to interview Maggie Smith. Very good.’ And you think, why didn’t you say more? It’s so annoying.”

Another recurring theme in the book is Liza’s lack of confidence in her own abilities. Kate explains: “A lot of people might say, don’t be ridiculous, of course she was confident. She was confident outwardly. If you met her, in her heyday, she was pretty and flirty and had a lot of character. Very funny, you know. She could really work up a joke, and she’d instantly be on it. So that was that confidence side of things. And even, I suppose a bit of, ‘well I made it with the books, I must be all right’.

“But then you read the diaries, and of course everybody writes the bad things in the diaries, so I had to put a bit of a filter on. But you get this, ‘I don’t know if I can be good enough, I really don’t, I don’t think I’m going to be able to do this’. And ‘other people are much better than me, or funnier than me’.

“I think that’s again, probably Granny, saying ‘Elisabeth, you’re not good enough for that’. You just don’t know what scars that leaves on people. But to be fair, Mum’s writing was not of the sort of first-class ilk of somebody like… Roald Dahl. I think she wrote as children enjoyed reading.”

What made Liza move into writing for children? “She desperately loved reading, and wanted to write. But probably recognised that she was not going to be writing adult fiction herself. She’d got the experience for children’s books. And again, it was economic; I think my father said, ‘go on, you can write children’s books, they make money’.

“Two great influences on her writing were E Nesbit, which she loved, and the Fairy Books. They were Victorian amalgamations of European fairy tale stories - The Blue Fairy Book, The Crimson Fairy Book, The Red Fairy Book, all wonderfully illustrated. They were terrific reading for a child. You like that bit of danger, it’s on their own or it’s feeling lonely, but it all comes out in the end, it works out for them.

“There was a very nice review in The Spectator Christmas edition. They asked well-known people what was their favourite children’s book. Justin Webb from Radio 4’s Today programme wrote Elisabeth Beresford, but it wasn’t The Wombles, it was Knights Of The Cardboard Castle. And interestingly, that was written about children who hadn’t got anything and they made the best out of things and they were unhappy at home. And it really resonated with him in that book. I think that’s what she had the gift for doing. So I hope that books like that, although they’re out of print, might not disappear entirely from people’s libraries.”

Perhaps most shockingly for Wombles fans, Liza’s diary revealed that the legendary Boxing Day walk on Wimbledon Common, during which she invented the Wombles, may in fact have taken place a week earlier!

“I don’t know whether she actually wrote that on the day, or whether it was one of her catchup things and she didn’t get it right,” says Kate. “I think of it as Boxing Day, but the more I think back, she may have been right and it was before Christmas. But maybe we went twice. Because Wimbledon Common is fantastic, where you can go and get lost and pretend you’re in the country and not hear a thing except birds. So I suspect that we went twice, and the two have got conflated.

“But I do remember, not because everybody’s told me this, but I remember we parked at the windmill. And I wasn’t a small child, I was about 14. So I was galloping down towards Queensmere, saying ‘Oh, it’s wonderful. Oh, I love it here in Wombledon,’ or whatever. As you do, you can get things muddled up.

“And Mum had been walking and thinking, and just ignited. And by the end of the evening, up in her study, she had worked out what it was going to be - not a story but who they were and what the ethos was. I suppose I was the trigger with that word, but she’d been thinking about something. So it might have been the ‘Wimbles’. But somehow they don’t sound quite so jolly and round, do they? ‘Wimble’ sounds thin.

“Of course there are some people whose surname is Womble. Quite a lot of people in Yorkshire, I think, who were rather cross. I suppose you get your leg pulled. But she didn’t know that.”

Most of the characters were based on members of the family, and named after places they had visited. What does it feel like to see your own family represented in the books and then on television?

“It was wonderful. I think it’s lovely because it perpetuates them. And it’s extraordinary how Bernard [Cribbins] brought them to life. He managed to sound like members of my family without ever having met them, which is amazing.

“I always feel that with Mum’s writing a bit of love creeps in whether she likes it or not, and that’s why people do like MacWomble the Terrible, because they’re recognising it as sort of a barky father. And that’s why they love Orinoco, because she put more of herself and my brother into that. Bungo was just bossy and slightly got sidelined. So I didn’t mind particularly, and Marcus doesn’t mind being Orinoco at all.

“But it’s perpetuated my grandfather [Alan Robertson], Great Uncle Bulgaria, who was lovely. And Uncle Aden, who’s Tobermory; we read in the biography about how he was always making gadgets and things, and worked on radar in the war. He was always very much that sort of character, which was terrific to use.

“And Granny, of course, Madame Cholet. She did a lot of cooking, which was delicious. I suppose you could say in modern parlance, it’s gender… assuming that she’s going to be in the kitchen. But that wasn’t the case then.”

Kate points out that it was Bernard Cribbins who gave Madame Cholet a French accent. “Bernard made her ‘ooh la la’. In the book she wasn’t French. So although it does work well in the films, in a way because of now, it’s a shame. Because we don’t want to have this sort of thing of being racist or sexist or whatever. Wombles should all be exactly the same, which they were, and you could say that Bernard was the first one to give them something else. And then Mum caught on to this and gradually there was Shansi, who’s Chinese, and the Canadians [at Cinar Films] of course wanted to bring in other ones, like Stepney and so on. It’s a shame, I think.

“Anything beyond Mum’s writing is a different kettle of fish. I feel that when various people have tried to take hold of the Wombles and make it theirs, the further they take the Wombles away from the family and the way she wrote them, the less likely they are to succeed.

“I’m glad to say I got hold of Bernard, and that must have been not very long before he died. He had written his autobiography which was a good reminisce, and he told me more or less the same thing as he put in there about the Wombles. But it was really nice to talk to him about it and we laughed, and it was like hearing Great Uncle Bulgaria and Orinoco and all that again for real, so that was lovely.”

The FilmFair chapter makes it clear how many redesigns and rewrites it took to actually get the TV series off the ground, to the point where the BBC were happy with it. What was that like?

“I interviewed Ivor Wood’s widow, Josiane, and she was very helpful and told me about Ivor. I’d met him a few times back in the 70s but not since then. So she and Barry Leith, between them, told me a lot about that period.

“There was that thing of, will it or won’t it work, with the BBC. But also, if you put too much pressure on, will it become something that nobody will want to watch, if they change it too much? There were so many constraints. But on the other hand, there were some really good things.

“And what would work on television; would it be the same as what works in the books? Not always - you need to be more visual. So it became more about the objects that they found rather than about the Wombles. And I think this is where Barry and Ivor were a huge help, because they could say what would work on television and how they could do it. And Mum knew the Common so well, she knew what would work, whether it was the umbrella blowing away, or The Times.

“Ivor was terrific, he was really good for her. When they were writing the scripts, she came up with the idea, or he and Barry would come up with some ideas, then she would write the scripts and then they’d tweak them. And then you would get Bernard doing his ums and his ahs.”

Having visited the set herself, Kate looks back on the show’s innocent appeal. “I do remember watching the Wombles being made. There’s something about the puppets and the tiny tabletop set. That’s what gave them such charm. Everything has been handmade, it’s just wonderful.

“And Great Uncle Bulgaria, he comes out of the burrow, the drawbridge comes down and he looks as though he needs two hip replacements! And then they’ve got that wonderful snout which Ivor designed - they hadn’t had it before that. And he looks down the specs, over the snout. They were so cleverly done.”

And then, how did Liza’s life change in the 1970s when the Wombles were a success? “Her life changed in that people are different towards you,” says Kate. “So some things got easier; people would go out of their way to help her to do things. Or they’d invite her to something. She used to go to the Women of the Year Lunches where all the well-known women of that period would be there. She liked the accolade, she’d been recognised.

“And she loved going on the [HMS] Ark Royal, and not only because it was the Navy. It was a bit of the adulation; they had a Womble as the mascot. So I think that was terrific, that things like that happened to her. And people wanted more books and stuff as well.

“The downside was that she had to work twice as hard. And she was at the beck and call of Wombles Limited, which was always having meetings which she found incredibly dull. And she’d constantly be asked for rewrites, then she’d have to do the annual… And she was still carrying on with the other books.”

This led to Kate helping out with some of the work. “She’d say ‘would you like to do some Womble writing?’ and I’d do a bit of the annual. So I did quite a bit of that. I enjoyed it because I knew the characters.

“I think actually when I wrote the Dilbert books at the end of the 70s, early 80s, I didn’t realise but I rewrote the Wombles. It was the same sort of characters because I’d got so into it. And Madame Concorde! The only trouble with Dilbert was that because he was a 747, he couldn’t do anything dangerous.”

Kate believes that her mother had undiagnosed depression, particularly evident after finishing a book or other intense activity. Liza would retreat to her holiday home on the small island of Alderney, eventually moving there permanently.

“She was really under strain. And Alderney was a great escape valve - she could go there and let the elastic go. She didn’t have a phone in the house to start with, so nobody could get hold of her. And I think she needed that. Because at one point she was really suicidal; she would just have too many people, too much pressure, too much Dad going off.

“Because that was the other thing that was happening. His star was falling and hers was coming up and that didn’t work well for either of them. He would expect her to be cooking for his friends, and she wasn’t because she’d got a deadline.

“I think the biggest change I can remember was, she went to Aspreys and bought herself a pearl necklace with a diamond clasp. And it was real, because she’d discovered that her engagement ring, which my father had given her, was not real. And she had paid for it herself - she had got there, to the point where she could. It was just some sort of tangible thing, that she loved wearing.”

Despite the relentless work, Liza loved talking to children and hearing what they liked about the Wombles. Kate says: “It was very, very busy. Suddenly you’re wanted to open this, that and the other, and she was always very good about talking to schools and libraries. And of course, the more she became known, the more they wanted.

“And she got an awful lot of fan mail. People would write to her from all over the world, and she always answered. Her scrapbooks are full of children’s stuff which they sent her. She was very good about writing back.

“She got very, very busy, enjoyed it and hated it at the same time, I think. And I use the word advisedly.”

How would Kate like her mother to be remembered? “I’m very pleased that I’ve been able to put the record straight, and whatever happens there will be information out there about Mum that is correct. And also that she is the creator of the Wombles, because I fear that in the future things can get changed. People are already referring to the original Wombles films as ‘based upon’ the stories but actually she wrote the scripts. And I hope that Wombles will go on for a long time.

“I’d like her to be remembered by children who have read and loved her books. And that doesn’t necessarily just mean the Wombles. Any child who’s loved that book and perhaps passed it on to its children. Or just, I’d like her to be remembered as somebody who wrote books that children loved.”

- Order The Creator Of The Wombles from Amazon or Pen & Sword Books

- More details about the biography